prism (ˈprizəm/) n. piece of glass or other transparent material cut with precise angles and plane faces. Prisms are useful for analyzing and refracting light (see refraction). A triangular prism can separate white light into its constituent colors by refracting each different wavelength of light by a different amount. The longer wavelengths (those at the red end of the spectrum) are bent the least, the shorter ones (those at the violet end) the most. The result is the spectrum of visible light, or the rainbow. Prisms are used in certain kinds of spectroscopy and in various optical systems.

Netflix is proposing I watch White Christmas. White Christmas is one of the many classics I watched with my grandma growing up. We would often screen films on American Movie Classics in the living room, after she popped popcorn on the stove. I got to know Rita Hayworth and Audrey Hepburn and Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire while curled up on that old brocade couch. I found the stylized nature of these films comforting, conjuring nostalgia for a time I never experienced first hand. The fancy dresses with foundation garments underneath, the finger-waved hair, the three-piece suits and wingtips and fedoras, the inexplicable breaking into song or dance at any moment. These glimpses gave me access to my young grandmother. The one with bright red hair and sweet collared dresses, who was a secretary after attending Washington University in her hometown of St. Louis.

White Christmas, released in 1954, features Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney, and Vera Ellen and is mostly a remake, in Technicolor, of a film made less than a decade earlier: Holiday Inn. Filmed in black and white, Holiday Inn was the movie that first introduced the world to the now-standard holiday song “White Christmas.” In the middle of the film, a cardigan-sweatered Crosby croons “I’m dreaming of a White Christmas” and pauses in playing the piano to reach over and ring the bells that are hung on the Christmas tree with a silver spoon.

The 1942 film revolves around two old buddies, Jim and Ted, played by Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire respectively, who used to have a musical act in New York City, who are intensely competitive, and who fall in love with the same woman, an aspiring performer Linda Mason, played by Marjorie Reynolds. Jim starts an inn in Connecticut—the Holiday Inn—that features monthly performances based on each month’s signature holiday. He hires his love interest Linda to perform alongside him. There is singing. There is dancing. There is a friendship strained by the friends’ mutual love of and competition for one woman. There is misogyny and stereotypical gender roles. And then there is the issue of blackness and whiteness.

I vaguely remembered the premise but mostly the feeling of sitting with my grandma in her living room when, a few years ago, I rented the DVD from a local video store. I remembered the costumes and the dancing, the coy smiles of this old school romance. I recalled the stunning solo number by Fred Astaire, who tap danced across the floor while throwing down firecrackers for the Holiday Inn’s celebration of the Fourth of July.

What I didn’t remember was the performance from Lincoln’s Birthday, which is astonishingly picked as the holiday for February instead of Valentine’s Day. Necessitated by the plot that requires Jim to disguise his beloved so as to ward off advances from his friend and competition, he makes a quick change and the number for Lincoln’s Birthday suddenly becomes a minstrel show. Bing as Jim emerges in blackface with a top hat, beard, and cane. Linda’s face is painted black as well and her hair spikes out into a myriad of ribboned blonde braids.

My jaw dropped. I had no memory of this scene at all. And I wondered: Was it because I was too young and had no context for what was happening? Did my grandma see the issues of the scene and choose not to tell me? Did she not see the scene as problematic enough? Did she avoid talking about it with me because of its problematic nature?

The song “Abraham” unfolds with Bing Crosby singing against a full orchestra also in blackface. The blackfaced banjo player sits in the far back on the ground. The waiters and waitresses are in blackface as well, the women adorned with kerchiefs and petticoated polka-dotted skirts.

The film also features a black housekeeper character named Mamie and her two young children, a girl and a boy, who also participate in the song. After Bing’s first verse, the camera cuts to Mamie. Holding her children on her lap, Mamie sings the question: “When black folks lived in slavery, who was it set the darkie free?” Her daughter sings a reply: “Abraham.”

Research reveals that some broadcasts began to show an edited version of the film in the 1980s. (How that worked I’m not exactly sure since this section of the movie also reveals crucial plot points. For example, that touching moment when Jim proposes marriage to Linda while painting her face black for the minstrel show.) Turner Movie Classics didn’t edit the film because they believe in broadcasting films as originally cut. And until more recently, American Movie Classics also ran the film in its original form.

This all makes me think I saw the original uncut version.

As offensive as this scene is, as horrible as it is to think that someone deemed it acceptable to create this musical performance and then use it as a lynchpin in the film, someone made that choice. Many someones. And to revise a cultural artifact that reveals its time, who was in power and what they thought, is dangerous. Revising texts in this way is to pretend that popular culture was not feeding into racist attitudes and actions.

But even more dangerous, I think, is the outrage so many white Americans often experience about the past that can nullify or desensitize us to the reality of the present. And our present involves a system that privileges and protects white people over and over again solely because of the color of our skin. Our present praises and makes permissible a system that results in the demoralization, degradation, dejection, and death of black and brown people.

Like so many Americans, I have felt devastated and angry this last week about the lack of an indictment of Darren Wilson in the killing of Michael Brown. When I returned home the night of the verdict, my desire to hit something was so strong that I ended up punching my mattress for a while. I felt a sickening feeling in my stomach, a combination of fury and grief, a few days later when watching the video that shows a Cleveland cop shooting and killing 12-year-old black child Tamir Rice a mere second after the officer got out of his car. There is no sound in the video so all you see is a small body standing upright and then crumpling to the ground. Devastating. Not to mention the local news story that led by attacking the character of the victim’s father instead of the confounding fact of an officer killing a child holding a toy gun. These deaths are tragedy accumulated because Michael Brown and Tamir Rice (and Trayvon Martin and and and) are not exceptions but part of a long line of African-American people killed in this country because of the color of their skin and because our country refuses to look at the reality and pervasiveness of the racism that we are founded in and on.

We would like to think we are so much farther along than Holiday Inn. But that’s just not true.

Only two weeks ago, Jacqueline Woodson was presented with the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for her book Brown Girl Dreaming, a memoir about growing up in South Carolina in the 60s and 70s, dealing with Jim Crow and the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement. And at this pinnacle moment of her career and artistic work, Dan Handler, the author of the popular Lemony Snicket series, made the joke that he “only just found out she was allergic to watermelon.” I can’t imagine what it would feel like, on one of the most important nights of your life, to have your accomplishments smeared with insults and reminders of the very injustices your work strives to illuminate.

Woodson responded in a New York Times editorial entitled “The Pain of the Watermelon Joke.” She traces her repulsion for the fruit as blossoming out of understanding its history. The fruit went from being tied to summer traditions, the lightness of family and childhood, to the rotting mess of racism. She writes, “…by the time I was 11 years old, even the smell of watermelon was enough to send me running to the bathroom with my most recent meal returning to my throat. It seemed I had grown violently allergic to the fruit. I was a brown girl growing up in the United States. By that point in my life, I had seen the racist representations associated with African-Americans and watermelons, heard the terrifying stories of black men being lynched with watermelons hanging around them…In a book I found at the library, a camp song about a watermelon vine was illustrated with caricatures of sleepy-looking black people sitting by trees, grinning and eating watermelon. Slowly, the hideousness of the stereotype began to sink in. In the eyes of those who told and repeated the jokes, we were shuffling, googly-eyed and lesser than. Perhaps my allergy was actually a deep physical revulsion that came from the psychological impression and weight of the association. Whatever it was, I could no longer eat watermelon.”

Woodson writes in the piece about how she realized her childhood dream of becoming a writer and about how she and Handler have been friends for years. She mentions that when he served watermelon soup at his Cape Cod home last summer, she told him she was allergic. Of his comments at her award ceremony, she writes: “In a few short words, the audience and I were asked to take a step back from everything I’ve ever written, a step back from the power and meaning of the National Book Award, lest we forget, lest I forget, where I came from. By making light of that deep and troubled history, he showed that he believed we were at a point where we could laugh about it all. His historical context, unlike my own, came from a place of ignorance.”

Ignorance of history and also denial of the significance of the small things in defining the large ones. A watermelon joke is not just a joke in the face of the history of that stereotype.

I am reminded of Sam Hamill’s essay “The Necessity to Speak” in which he talks about witnessing violence in the form of war, domestic violence, the criminal justice system, and abuse. When discussing domestic violence, he references popular culture’s complicity in and condoning of it. He writes, “When James Cagney shoves half a grapefruit in a woman’s face, we all laugh and applaud. Nobody likes an uppity woman. And a man who is a man, when all else fails, asserts his ‘masculinity.’” All forms of oppression are different but all oppressed groups are ultimately linked. And they are linked by the times in which someone said or did something oppressive and demeaning that an onlooker decided was no big deal. Oppressions are linked by slurs and taunts and side-glances and critics that say: “aren’t you taking this a little too seriously?” and “can’t you take a joke?”

Back in August immediately following Mike Brown’s shooting, Jon Stewart closed a segment of The Daily Show called “Race/Off” by saying: “Race is there and it is a constant. If you’re tired of hearing about it, imagine how exhausting it is living it.”

The media reporting of protests surrounding the lack of indictment in Ferguson have focused largely on the “mobs” of people, on the intensity of people’s anger, and not on the reason for their fury. There have been some wonderful articles comparing the difference between why white people riot (winning or losing sporting events) and why black people riot (verdicts like “not guilty” for Zimmerman or “no indictment” for “Wilson,” i.e. no justice for innocent black people being killed). I am reminded too of the two almost identical photos published just after Katrina: one of two black people and the other of two white people wading through water with food from a flooded grocery store. The captions revealed that the black people were “looting” and white people were “finding food.”

Last weekend, before the grand jury released its ruling, I read Claudia Rankine’s new book Citizen: An American Lyric. Through lyrical prose about her personal experiences, politics, and pop culture, Rankine explores the perpetual presence of racism in the lives of African-Americans and the extent of the damage it does. On the front cover is a white backdrop with a black hoodie torn from its torso.

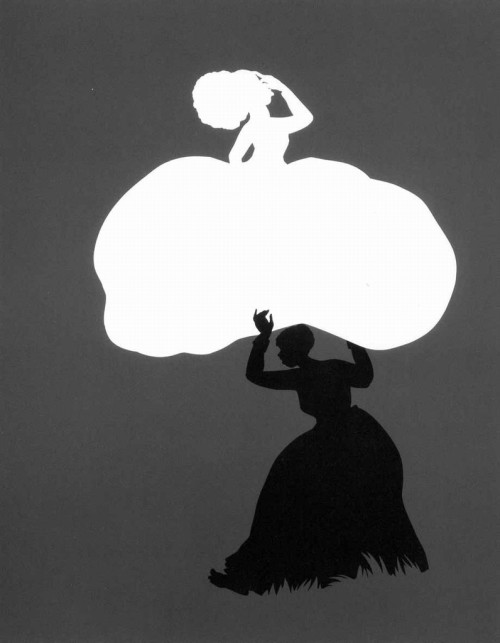

Except for the last page, written in first person, the book is in second person: firmly placing the reader in the slot of “you.” She writes in one section about Hennessy Youngman, aka Jayson Musson, who, in youtube videos, “advises black artists to cultivate ‘an angry nigger exterior’ by watching, among other things, the Rodney King video while working.”

She continues: “Youngman’s suggestions are meant to expose expectations for blackness as well as to underscore the difficulty inherent in any attempt by black artists to metabolize real rage. The commodified anger his video advocates rests lightly on the surface for spectacle’s sake. It can be engaged or played like the race card and is tied solely to the performance of blackness and not to the emotional state of particular individuals in particular situations.”

“On the bridge between this sellable anger and ‘the artist’ resides, at times, an actual anger. Youngman in his video doesn’t address this kind of anger: the anger built up through experience and the quotidian struggles against dehumanization every brown or black person lives simply because of skin color. This other kind of anger in time can prevent, rather than sponsor, the production of anything except loneliness.”

“You begin to think, maybe erroneously, that this other kind of anger is really a type of knowledge, the type that both clarifies and disappoints. It responds to insult and attempted erasure simply by asserting presence and the energy required to present, to react, to assert is accompanied by visceral disappointment: a disappointment in the sense that no amount of visibility will alter the ways in which one is perceived.”

I want to repeat her words again: “anger is really a type of knowledge, the type that both clarifies and disappoints….a disappointment in the sense that no amount of visibility will alter the ways in which one is perceived.”

I read an article recounting an event in St. Louis following Mike Brown’s shooting where ten black mothers sat and talked to an audience full of mothers—of different ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds—about the experiences they had in talking to their children about race and racism. Director of Racial Justice at the YWCA in St. Louis Amy Hunter told a story about a time when her son was 12 and noticed a police officer following him as he walked. He was only five blocks from home. When he arrived and told her what happened, he asked, “I just want to know, how long will this last?” She cried as she relayed to the audience what she told him, what she had to tell him: “For the rest of your life.”

Can we just think about that for a second? That for his whole life, this child, this mother’s son, this boy then young adult then man, this human being will have to walk the “right” way, say the “right” thing in order to attempt to preserve his life. And even if he does everything “right,” he is still at risk of being harmed or killed solely because of the color of his skin. How many more lives lost? How much more will it take for us to change a system that is harming and killing so many citizens of our country?

I understand that, as a white person, my perspective is limited and that I cannot fully understand the grief and anger of black individuals and black communities in seeing this same injustice and violence perpetuated over and over again. I felt myself paralyzed this past week with what to say in relationship to this, wondering when and if I should write anything at all.

I grew up in New Orleans, a city segregated by color lines. And without anyone ever needing to really explain the idea of separate and unequal, I saw it everywhere. And what I mostly saw was good-hearted white people pretending that nothing was happening. This is happening. People of color are being killed and oppressed solely because of the color of their skin. This is happening. The criminal justice system is rigged against minorities and people of lower socio-economic status. This is happening. Black kids are being killed while white kids are being given the benefit of the doubt. This is happening. People of color are not “playing the race card,” people of color are being played, by a system rigged to oppress them.

I believe that many Americans will look back at this time and be as appalled as we are now by lynchings, by blackface, by Interstates built through African-American communities. That’s not good enough, to hope that one day we will look back and be appalled. Let’s be appalled now. Let’s do something to change this.

Before Isaac Newton, people believed that pure light was colorless and that light was “altered into color” from interaction with matter. Experimenting with prisms using refraction, Newton revealed the opposite, that light included within it the whole spectrum of color. That a prism didn’t create color but rather separated it, showing what was already present.

In ophthalmology, prisms are used to diagnose and treat deficiencies and diseases of the eye. Ophthalmologists use light reflected and refracted by prisms to examine the eye for vision problems so they can be treated. It is only in altering angles, in finding mirrors, in looking in different ways that problems can be identified, that vision can become clear.

Here are some pieces I found insightful/helpful/encouraging/profound in reference to Ferguson:

On Ferguson Protests, the Destruction of Things, and What Violence Really Is (And Isn’t) by Mia McKenzie

Telling My Son About Ferguson by Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow

It’s Incredibly Rare For A Grand Jury to Do What Ferguson’s Just Did by Ben Casselman

Twelve Things White People Can Do Now Because Ferguson by Janee Woods

This Is What Darren Wilson Told the Grand Jury About Shooting Michael Brown by Jaeah Lee and AJ Vicens

“Not An Elegy For Mike Brown”: Two Poems for Ferguson by Danez Smith

Ferguson isn’t about black rage against cops. It’s white rage against progress. by Carol Anderson

Interview with Mike Brown’s parents

Claudia Rankine’s amazing book Citizen.