cells in dish replicate schizophrenic brain

schiz·o·phre·ni·a (skitsəˈfrēnēə), n. [Mod. L. < schizo- + Gr. Phren, the mind] a mental disorder characterized by indifference, withdrawal, hallucinations, and delusions of persecution and omnipotence, often with unimpaired intelligence: a more inclusive term than demtnia praecox, avoiding the implications of age and deterioration.

For the second word this flash fiction february, we are honored to have pieces authored by two writers: Elizabeth Frankie Rollins (first) and Rebecca Iosca (second).

(In French, “aliéné” Means Mad)

Eloise couldn’t say. The teachers asked. The classrooms felt immense. The teachers and the students seemed like giants moving around her. In her French class, Eloise stared at a worksheet in front of her and the accents on the words looked like eyebrows. She couldn’t read one French word, although she knew she used to be able to read some of them. Now they looked like simple black marks. She could barely fit the French words the teacher spoke into her head. They were too big. She wanted to put her hands over her ears, but she didn’t. This would make them ask her more questions.

She didn’t want to think about it.

At lunch, she received her tray of macaroni, red jello square, and paper milk container, but she couldn’t remember where she usually sat. She chose a table with girls. As soon as she sat, as soon as they began ignoring her, she remembered that this wasn’t her usual table. She’d only been gone a couple of weeks, but couldn’t remember things. Even the air felt too big. It hurt her ears.

There had been a lot of screaming. But no, she didn’t want to think about it.

In science, they stood over plastic tubes and looked at liquids. Her paper, where she was supposed to fill in the blanks with numbers, remained blank. She didn’t even look at other students’ papers to fill hers in. She stood at the table and stared at what they did, but she couldn’t put anything in the white blanks on her paper.

There had been a lot of messes. She hadn’t cleaned them up. No one had. Everything got sticky.

The Vice Principal came to check on her in the homeroom at the end of the day. The Vice Principal’s first name was Barbara. Eloise read this on the nametag, but she couldn’t pay attention to the last name. Barbara the Vice Principal crouched in front of Eloise and spoke. Her breath smelled like coffee and bologna. Eloise was sick of breath.

There had been a lot of strong breath: whiskey breath, wine breath, stale breath, weeping breath, smoking breath, screaming breath.

Barbara the Vice Principal said something about Eloise’s mother. Eloise stared at her. She felt the air swallow her up, as if she was shrinking, as if her head was folding down on itself. She stared at Barbara the Vice Principal, who said, “I can understand if you aren’t ready to talk about your mother yet, but I want you to know if you want to talk about it with me, any time, you can.”

There had been a lot of talk about things Eloise didn’t understand. Real estate, avocado growers, pantyhose, poisoned water, why people should learn French, why no one should have telephones, what good girls did, who was a really great singer, and people out to get you.

When Barbara the Vice Principal asked, “Eloise, are you listening?” Eloise couldn’t say.

The dinner table at the Gershens was set with plastic tablemats picturing strawberries with legs. Folded paper napkins sat on the mats, and forks and knives on top of the napkins. It was only Eloise and Mr. Gershen and Mrs. Gershen at the table. They didn’t have children. There was meatloaf and orange macaroni and cheese and a very big piece of broccoli on Eloise’s plate. Eloise ate some of everything. She knew that you had to plan meatloaf. You had to cook it in the oven. She knew it wasn’t easy, she knew that cooking wasn’t easy. She understood that some things weren’t easy and you shouldn’t ask for them. But she hadn’t asked for this and she liked it.

There had been food, but usually it was “craving” food. Craving food came in greasy paper wrappers or sticky sweet cellophane. In cardboard boxes or styrofoam bowls. If you didn’t eat it fast, you weren’t really craving it, and you shouldn’t take it from the people who were craving it.

There had been a lot of smoking and the ashtrays got really full and spilled onto the table or counter. There were a lot of ashes on the floor, too, from cigarettes being waved around. Eloise washed her feet sometimes, when they turned black on the bottoms.

There had been crying and apologies and yelling and then the longest silence. It was the longest silence that sent Eloise to the neighbors and then the police came, and an ambulance, and Eloise had not even gotten to say “good morning,” or “good bye” and now she was living at the Gershens and she’d gone back to school as if nothing had happened but everything had happened and she hadn’t even said “good bye” and now she had to go to French class where nothing made any sense at all, though everyone else pretended like it did.

Eloise took the clean dishtowel with smiling kettles and teacups and wiped the plates that Mrs. Gershen handed her. She wiped them dry, around and around and around. Mrs. Gershen took them from her and placed them neatly in the cabinet. Click. Click.

Mrs. Gershen turned and looked down at her and said that there had been a call from the hospital where they were keeping her mother for observation, but Eloise had not even said “good morning” or “good bye,” so she stared hard at the framed needlepoint on the wall which said Gershen in fancy letters, circled by mice and cheese and mustard pots. The mustard pots were white with red stripes around the rims. She nodded when Mrs. Gershen stopped talking and handed back the kettle towel.

When Mrs. Gershen asked, “Eloise, we all want to help you, you know that, don’t you?” Eloise couldn’t say.

Elizabeth Frankie Rollins has published work in Conjunctions, Green Mountains Review, Trickhouse, The New England Review, and The Cincinnati Review, among others. An excerpt from her novel, Origin, will soon appear in Drunken Boat. Author of The Sin Eater, Corvid Press, she’s previously received a New Jersey Prose Fellowship and a Special Mention in the Pushcart Prize Anthology. She teaches writing at Pima Community College and the University of Arizona Poetry Center. Installments of Origin and short fiction can be found here: www.madamekaramazov.com

cells in dish replicate schizophrenic brain

Rosemary, in LA I became you. Some memory of the way you rode the bus away from home, from your father really, who scared you so badly you hid under the table. The first time they thought something was wrong it wasn’t because you were scared (they both knew he could be scary even though they never admitted it to you), but because you were meowing, quietly at first and then with more feeling, crouched under the table. You were twelve. Did he tell you then to become an actress because you were being so dramatic? I don’t know if he ever hit you, but I know you tried to snap a woman’s neck once and almost succeeded. You walked like you were still 300 pounds, but you’d lost weight and all of your teeth. Or maybe it’s more true to say that when you’d lost most of them, the rest were pulled. It was the only service covered by your dental plan by then.

No wonder you were angry. The side effects of how you had to live would be enough to make me angry, but to think directly of the main axes of truth in your life. Or if not truth, some version of mundane reality. Locked up in a building that smelled of far-gone yesterdays and surrounded by paint shades too dark to catch the little northwestern light that landed in your room. The one chair out on the smoke-porch that was the only one you understood. You got in fights about it because nobody could understand you having a chair that was the only one you understood. Your mother sent you things you might need at logical intervals, but there were no cards, no little gifts, no Christmas presents even though you still counted down the days gleefully every year. What you called “giving birth,” the rest of the world called “having an accident in the middle of the night.” Your baby, then, a yellow stain that no one wanted to manage. In the morning after so many of my arrivals, plastic gloves, biohazard bags, and a trip to the laundry room. But not after you told me her name. It was usually the same each time: “little glow.” Years later, I learn of the Spanish phrase “to give a light” for birth, and I think of the landscapes you won’t ever see.

By the time you were 18, you’d hopped a bus to Hollywood, but your chart said nothing else. You spoke of acting, and I can imagine a time when catching a break in Hollywood seemed plausible or at least possible. I would have believed you were a model. In your face, a deep beauty and in your movements an unswerving confidence. But you told me you were on that cruise the year before I met you, when you had already lost your teeth, already lost so much more than your teeth. You looked so happy recounting the places you’d visited, and I wondered then about whether it wasn’t something of a blessing to remember a history that is not your own. A kind of imagination-in-reverse function. If your days are spent smoking cigarettes until your fingers yellow and finding your only real comfort is a stuffed horse who sits on your narrow bed in your narrow, urine-soaked room, how obliging of your mind to take you on a cruise, show you the beauty of the world, reflect your beauty to you in the eyes of off-stage admirers? How obliging of your mind to give you a baby every morning instead of a mess to clean up and the knowledge that your body is past being able to carry one.

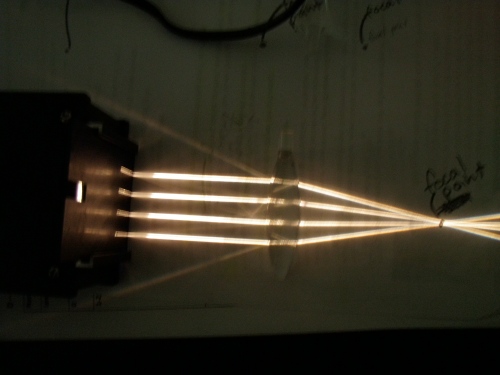

I was not in Hollywood, but in LA I saw trees like prehistoric towers lining the streets and watched a film in 3-D about Pina Bausch. In the theater I became you, for a moment, seeing the world in front of me in blurry multiple, edge over edge, until I put on glasses that made the multiplicity three-dimensional and single. I want to say singular, and it was that too. I felt, suddenly, your frustration at trying to explain that the world is round and alive and moving quickly toward you when everyone else could see only blurry flatness taken for the extent of what was there to be seen. It’s a wonder you never gave up trying to explain what was there for you, in stereo, in stereoscopic 3-D, as we unfocused our vision, trying to make the world as we knew it more clear or at least contiguous. And who would have believed you anyway, if you’d somehow managed to fashion paper spectacles with blue and red lenses, and shouted triumphantly that finally we might see your reality? You probably would have been written up, the glasses discarded as a quaint craft project or some other artifact of delusion.

When people say “schizophrenic,” so often what is heard is “split,” “broken,” or “out of touch with reality.” Your diagnosis was based on the concept of emotions split from thought, but who can say what emotions are called for anyway, or who is more colonized by perplexing delusions than anyone else? And who is to say what of reality there is to touch, and what edges, what whole planes in fact, we might be missing in our smug perceptions? Can empiricism explain the way you spoke of my father, but never my mother, except to say, at times, that you were my mother? Can scientific inquiry measure the chances that of all the names you could have taken on once you were sent away to the state hospital, you chose my mother’s and called for me like I was your daughter?

Rebecca Iosca feels grateful to have become friends with Lisa, the resident logophile of The Dictionary Project, through the University of Arizona’s MFA program, and has worked with a number of amazing people who happen to be diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Rebecca Iosca feels grateful to have become friends with Lisa, the resident logophile of The Dictionary Project, through the University of Arizona’s MFA program, and has worked with a number of amazing people who happen to be diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Born and raised in New Jersey, Alison McCabe lives and writes in Tucson. She teaches English at the University of Arizona where, in 2010, Alison received her MFA in Fiction. She is currently at work on a novel.

Born and raised in New Jersey, Alison McCabe lives and writes in Tucson. She teaches English at the University of Arizona where, in 2010, Alison received her MFA in Fiction. She is currently at work on a novel.