On this last day of november and for our last post of nonfiction november, we are excited to share this piece by PR Griffis on Xanadu. Enjoy!

Xan·a·du /ˈzanəˌdo͞o/ n. a poem by English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge: an idyllic, exotic, or luxurious place.

XANADU

I was eight years old in 1980 when Xanadu, the film starring Olivia Newton John, was released. I don’t remember much of the film itself—something maybe about Greek goddesses come to life through a billboard and arriving in sunny Southern California to rollerskate. It seems like maybe there was an older gentleman who wore a yachting outfit, or maybe that was one of those B-list-star-filled episodes of CHiPs.

Two things are important to me where Xanadu, the film, is concerned. First, I was in love with Olivia Newton John, and had been since I saw Grease at the drive-in two years before. She might have been my first cinematic crush. Good girl, poodle-skirt, bobby socks, and saddle shoes Sandy, or teased hair, black leather, high spiky heels Sandy, either one. As with Bewitched, where Elizabeth Montgomery played both blonde housewife witch Samantha and Aquarian-age party-girl witch cousin Serena, it was only different flavors of the same thing, each impossibly lovely in its own way.

Second, the thing I remember best about Xanadu is the title song from the soundtrack, sung (natch) by Olivia Newton-John. This, of course, only a year or so before “Let’s Get Physical.” Which: yes, please.

I was surprised and saddened as a child to discover that Olivia Newton-John and Juice “Angel of the Morning” Newton weren’t related. I was particularly taken with female singers—Crystal Gayle, Patsy Cline, Loretta Lynn—especially of the crossover type, of which there were a plethora in the late 1970s.

“Xanadu,” the song is, if you’re not familiar with it, a dreamy disco tune, ONJ’s voice undulating beneath swirling veils of layered synth. It is also personally notable as the first instance I can recall of misapprehending lyrics. I was maybe twenty before I came to understand that what I had heard as testing me wasn’t right was actually destiny will arrive.

“Kubla Khan,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, from which Xanadu enters the western lexicon, is notable for beginning with the workmanlike slack-stress metrics of which junior high poetry unit horrors are made: In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure dome decree.

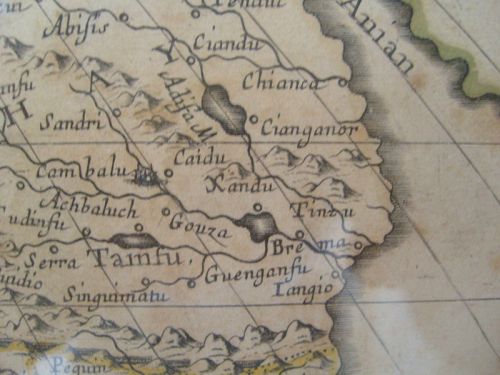

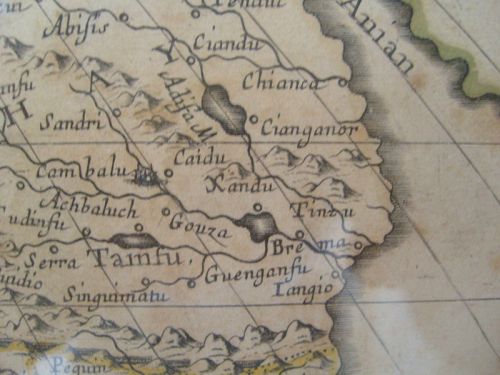

Coleridge claimed to have received the inspiration for “Kubla Khan” after reading Purchas, his Pilgrimage, or Relations of the World and Religions Observed in All Ages and Places Discovered, from the Creation to the Present, which ponderously-titled book details the travels of Marco Polo, who is believed to have visited Xanadu, the summer palace of Kubla Khan, ruler of Mongolia and part of China, in the late 1200s.

Also notable: Coleridge had administered himself “an anodyne for a slight indisposition” (read: opiates) and fallen asleep for a few hours after reading Purchas. The poem, he claimed, came to him fully formed during this sleep.

So, after a three-hour dope nod, he roused and wrote “Kubla Khan” the place of stately pleasure domes, the place of sacred rivers running through caverns fathomless to man.

Did I first play Marco Polo at about this same time—eight or nine years old—or shortly after? When was it that I first assumed the role of blind explorer, navigating chest deep and unseen water, attempting to reach far-flung and ever-shifting ports of call?

Coleridge claimed to have been interrupted in the midst of his writing by a man on business from Porlock, the remainder of the poem evaporating, the phrase “a man on business from Porlock” now a synonym for interrupted genius.

Grease was my favorite movie when I was seven, in 1978; “Xanadu” was my favorite song in 1980, when I was nine. Somewhere in there was Charlie’s Angels. I was in love with Kate Jackson, Jacklyn Smith, and Farrah Fawcett, in that order. I knew, deep down, I was supposed to be in love with Farrah Fawcett, if for no other reason because she was married to the Six-Million-Dollar Man, Lee Majors. She was, during this time, Farrah Fawcett-Majors.

One has to imagine that transoceanic travel, travel east from Europe to Asia in general, must have been fairly dodgy if Columbus, some two hundred years after Marco Polo’s voyage, tried to establish a route by heading in the opposite direction. Travel of that sort at that time being akin to—maybe even more dangerous than, statistically speaking—the space travel of our own age. And certainly, the desire to boldy go where no man has gone before, the human yen for discovery—equal parts a pull of the unknown and a pushing away from the known, the ultimately unsatisfactory—is well documented throughout human history.

Zeitgeist, maybe, is nothing more than a convergence of arrangements from possibilities theretofore nonexistent or inaccessible. Marco Polo, certainly, enlarged the realm of possibilities through his travels to and return from Asia, as did the introduction of culture and technology represented by the Moorish conquest of Iberia. Would the transatlantic voyage of Christopher Columbus have been within the realm of possibility without these happenings? Is it coincidence that the reconquista of the last Moorish-held Iberian lands and Columbus’s voyage both occurred in 1492?

2001: A Space Odyssey was released in 1968, three years before I was born, the year before men landed on the moon. Interestingly, Elton John’s “Rocket Man,” David Bowie’s “Star Man,” and Lou Reed’s “Satellite of Love,” all of which take as their subject matter space travel, all came out in 1972. It’s as if these songs are the product of some Aquarian age that had as its focus some tenable objective correlative, a means by which we might transcend the bonds of space and time, some century after time and distance had been shattered by means of the telegraph and railroad, the means by which we might realize a place where we could make ourselves anew.

The Velvet Underground’s 1967 “I’m Waiting for the Man” is about scoring dope in Harlem, a venture much less dodgy than traipsing through Mongolia in the late 1200s, to say nothing of (a diminuendo, voices dying with a dying fall beneath the music from a farther room) rocketing into outer space.

When I was seven, my best friend Weldon and I used to take turns being Farrah Fawcett and Lee Majors. His bed was an ocean, the sheets were the waves, and we would dive under the water and kiss open mouthed. Because we were only aping what we’d seen on TV, we didn’t know that there was supposed to be tongue involvement. I don’t remember either of us being concerned who was Lee Majors and who Farrah Fawcett-Majors.

In 1980, it was Xanadu and Olivia Newton John. By 1981, I wanted to see The Road Warrior more than I wanted anything. The next year, Conan the Barbarian came out, and I wanted to see that more than anything.

Does it reflect some grimmer reality in the national zeitgeist, this trending away from disco, from dancing, from musicals and magic? Or is it a graphing of the process by which a boy who saw no difference between playing with Barbies and GI Joe, a boy with no firmly fixed gender predilections, learned his place?

Travel, journey, being the primary means by which American narrative is given structure. If you are dissatisfied with your lot, move. Move from Europe to the Americas. The primary motivation of the Spanish foot soldiers who first came to the Americas—a journey from which they might not return—was the promise of land, of gold, of glory, all of which are ways of saying opportunity. Move. Move from the East to the Midwest, the South, the West. Move out onto the oceans and hunt white whales, move out onto the plains and hunt buffalo and first peoples and precious metals and one another.

And once even space and ocean have been thoroughly explored, begin in earnest the inner exploration, the exploration that does unto self what exploration did to the oceans and the west and the south and the east. Rocket off into inner space. Is it coincidence or convergence that syringes and Saturn rockets bear a striking resemblance to one another?

Xanadu, now, is a synonym for paradise. The final frontier, inner or outer. When we were twelve, my friend Robert and I rode our bicycles out into the country—white rock roads sectioning off ten-square-mile tracts of farmland—and found a low water crossing that emptied into a small pond. The idea of a place where water washed over the road and into a small limestone pond, wreathed round with willows, it was almost too much for the mind to bear. I decided that we would call it Xanadu. Because this is what we do with places that were already there when we arrived. We name them to suit us. We name them in keeping with the breadth of our understanding (see: The New World).

I didn’t know what to call the thing I discovered I could bring into being when I was nine or maybe ten, a year or two after we’d moved to a new and smaller town, where I was at first and for some years largely friendless. Call it The Man From Porlock. Call it Xanadu. Call it The Autoerotic Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Another kind of blind exploration, in any case, there in the dark of my bedroom. Marco. Polo.

How elegant the space station in 2001. How workmanlike, how quotidian, the International Space Station. How sad that our grasp for the stars has been shuffled off, that astronauts from the country who first put men on the moon now have to fly coach. How strange that some three short years after Kubrick realized his masterpiece of humanity’s uneasy relationship with technology, that technology became firmly means to end, just one more way to speak of distance, a means of metaphor.

The space program having, of course, its roots in the Nazi V2 rocket program, the same technology used to propel our most ardent aspirations towards the stars was wedded to one of the dirtiest moments in US history, another product of World War II. Little Boy, all grown up and become the ICBM, with something like 500 times the destructive force. Perhaps the fact that Russian and American scientists now work side-by-side in the ISS is a step towards the kind of utopian ideals embraced in, say, Star Trek.

Robert and I figured out later that the creek that supplied the water to Xanadu—our found and primeval paradise—ran through a cow pasture. Which meant that the water in Xanadu, in which we’d swum and splashed with such abandon, was chock-full of cow shit and all other manner of agricultural effluvia.

David Bowie, of course, released “Space Oddity” in 1969, the year after (and inspired by) Kubrick’s release of 2001: A Space Odyssey; “Space Oddity” introducing into the lexicon the figure of the lost astronaut Major Tom.

Odysseus, of course, being a Greek soldier who had a hell of a time getting home from the Trojan War.

In 1980, Bowie sings “Ashes to ashes, fun to funky/ We know Major Tom’s a junkie.”

Coleridge wrote to John Thelwall in 1797: “I should much wish, like the Indian Vishnu, to float about along an infinite ocean cradled in the flower of the Lotus, & wake once in a million years for a few minutes… I can at times feel strong the beauties you describe… but more frequently all things appear little – all the knowledge that can be acquired child’s play – the universe itself – what but an immense heap of little things?

Time speeds up as we age. The hours before it is permissible to wake one’s parents on Christmas morning, the last few weeks of summer vacation, when no more swimming or playing or reading or sleeping will satisfy—sated with relaxation—these lasted lifetimes. Now, months pass in no time at all. The three and a half years I spent in the Army, the four years I spent in high school, these seemed like a million years. Everything—time, distance, suffering, joy—is relative, is how I understood Einstein’s theory. Who, for instance, is to say a three-hour dream of paradise is not one million years slept and awoken from?

Weldon was not the last guy I did stuff with. Into my early teens, I dated girls, and I experimented with boys. Girls were terrifying in their terra incognita, as boys were terrifying in their potential, should our experimentations become public knowledge. The small Texas town where I grew up having clearly defined boundaries, and fairly heinous standards and practices for people who transgressed them, I wasn’t certain enough in my orientation—a Kinsey Scale 2, say—to risk the potential for social and physical harm to act any further than I did on what was, in any case, more curiosity than identity.

A few years after Robert and I discovered Xanadu, we found an abandoned limestone quarry outside of town. There were a couple of places where the water was deep enough to jump off the ledges into the pools below. If you hit the bottom, though, it raised up purplish clouds that gave off an awful stink. After we’d been swimming there for awhile, we saw the rancher whose farm the quarry bordered dumping a wheelbarrow-full of horseshit into the water from just about the spot where we usually jumped.

I traded one identity for another, always, I think, wanting to feel safe. To feel accepted. Musicals for post-apocalypse, disco for metal, extroverted and nerdy for stoned and jockish, push-ups and sit-ups for things that worked faster and more reliably, gender-fluid for gender rigidly defined.

Growing up in an agrarian community in Central Texas, my youth was at least somewhat defined by small bodies of water and the presence of animal shit. That, and an uneasy relationship with gender, with White Male Power that probably defined—necessitated—my movements outward, onward. As with Marco Polo, as with the conquistadors, as with Lou Reed and David Bowie and Elton John, I had to move, pushed as much as pulled. I was defined by all of these, and that discovery of personal Xanadu—and what is paradise for us here on earth but a moment’s reprieve, one moment being all we have at any time—of a dozen different sorts, of personal erasure and continuous making anew.

PR Griffis lives and writes in Willimantic Connecticut with his wife, the writer Mika Taylor, and their dog, Petunia Von Scampers. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fuse, Diagram, Defunct, and Devil’s Lake. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel of as-yet-undetermined length, and sometimes attempts to Twitter: @PR_Griffis

PR Griffis lives and writes in Willimantic Connecticut with his wife, the writer Mika Taylor, and their dog, Petunia Von Scampers. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fuse, Diagram, Defunct, and Devil’s Lake. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel of as-yet-undetermined length, and sometimes attempts to Twitter: @PR_Griffis

Debbie Weingarten is a graduate of the funky and beautiful Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, North Carolina, where she received degrees in Global Studies and Creative Writing. She currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she grows vegetables, makes babies, organizes on behalf of small farmers, and aspires to one day finish a collection of short stories.

Debbie Weingarten is a graduate of the funky and beautiful Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, North Carolina, where she received degrees in Global Studies and Creative Writing. She currently lives in Tucson, Arizona, where she grows vegetables, makes babies, organizes on behalf of small farmers, and aspires to one day finish a collection of short stories.