flo·ta·tion (flōˈtāSHən) n. [earlier floatation, respelled as if < Fr. Flottatison], 1. the act or condition of floating or launching. 2. the act of beginning or financing a business by selling an entire issue of bonds, securities, etc.; hence, 3. the act of beginning; becoming established. 4. in mining, a method of ore separation in which finely powdered ore is introduced into a bubbling solution to which oils are added: certain minerals float on the surface. And others sink. Also spelled floatation.

And from another definition: “involves phenomena related to the relative buoyancy of objects”

Thoughts on floating, in three sections

I.

It is difficult for us human types to be buoyant when water is not involved. There is a gravity to us, not just the weight of our skeletons, our sinew and tendons and muscles. There is a gravity to the way we think about and interact with the world. Just the nature of our consciousness and our ability to consider ourselves, to reflect on our lives and our relationship to other lives, means that we hold ideas and concerns within us that weigh us down. I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing. Without weights, balloons fly off into the sky. Being grounded is often a necessary, satisfying feeling. Some of the poses that feel most challenging to me in hatha yoga are balancing poses, where I am required to suspend most of myself in the air without both feet firmly planted on the ground. There is satisfaction in rooting.

However, I do think there are moments when we need to be able to experience lightness to balance out the things that keep us weighed down. For hundreds of years, different seekers have tried to achieve a greater form of lightness.

English scientist Henry Cavendesh isolated hydrogen in 1766 and doing so, commented on the idea of “negative weight” and the possibility of lifting objects above the earth.

The hot air balloon was invented by French brothers Joseph and Jacques Montgolfier seventeen years later. This invention began as a smaller experiment when they found that in filling a silk bag with hot air, containing less density than the air surrounding it, it rose to the ceiling. They created a larger bag to hold the air, attached a basket and sent several farm animals aloft. A few months later, they launched a seventy-foot high balloon that raised Jean Francois Piltre de Rozier and the Marquis d’Artandes three thousand feet above the ground. One hundred and twenty years prior to the Orville Brothers’ first successful flight by plane, these men were the first to have that feeling of rising far above the ground and being held by the air, of being sustained in a sort of static flight.

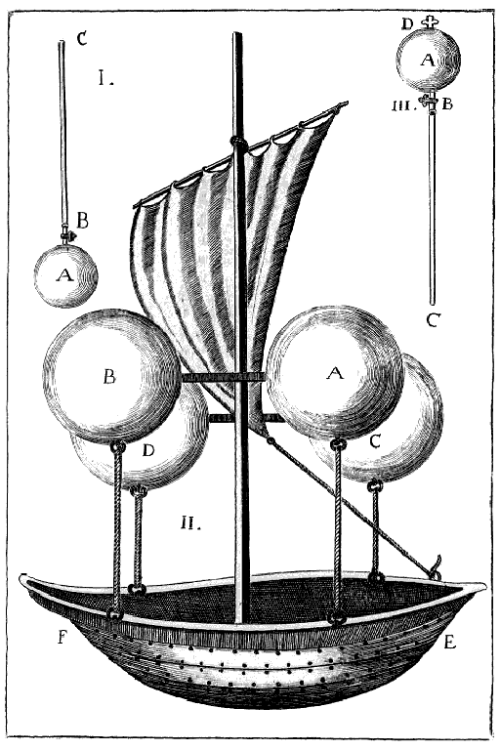

But long before this hot air balloon flight, Francesco Lana de Terzi, an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician and

naturalist, designed his own airship, one that moved from force of wind in the bellows. He is often referred to as the Father of Aeronautics for his designs, innovation and exploration and for legitimizing aeronautics as a field of study. The airship design itself resembles a sea ship, with its crescent sails and curved boat-like bottom. Instead of moving through water, this ship would navigate the sky.

By 1663, he had developed plans for his airship and published them in a book. His invention was designed after and would be steered as if it were a sailboat. The ship was to be made of a central mast with a sail attached and four smaller masts to which were attached copper foil spheres. He calculated the size of these spheres and the air that would be pumped inside them, in vacuum conditions, so that they would be less dense than the air surrounding them. No one had the capacity during his time to manufacture the thin copper foil. As it turned out, no such capacity exists. Even if done in vacuum conditions, the pressure of surrounding air would immediately flatten the thin metal.

The idea itself was problematic even to its inventor, but for other reasons besides actualization of the design. De Terzi expressed concerns that the ship could be used ultimately as a weapon in war, saying, “God will never allow such a machine be built…because everybody realizes that no city would be safe from raids…iron weights, fireballs and bombs could be hurdled from a great height.”

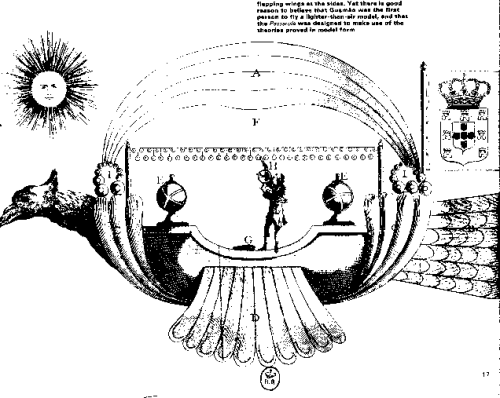

Fellow Jesuit priest and Brazilian naturalist Bartolomeu de Gusmão redesigned an airship, in the tradition of de Terzi, and in 1709, he shared his secret plans and blueprints with King John V of Portugal. His design was for a large sail to be spread across a boat-shaped base like a rainbow. The momentum of the vessel was to be derived from magnets in two balls on either side of the ship. The planned public test of the machine never took place, but some reports say that he did more informal experiments and was able to make the vessel fly. Gusmão later worked on a newer invention of an airship, with a gas-filled pyramid above the vessel, but he died before he could bring his design to fruition.

I think about these thinkers and inventors and their desire to sail through the air. They had the yearning be above the ground, not merely for a given practical purpose but for the experience of it, the change in perspective, the ability to see the earth that we know assume a different shape as we rise above it.

There is a beauty to the way that we humans constantly try to defy our own gravity. We jump on trampolines, we bungee jump, we suspend ourselves from ropes, we hang on trapezes, we fly in airplanes and helicopters, we parasail, we gondola, we zipline. We manufacture all kinds of ways where we experience freedom from the ground, where we experience little more than air encasing our bodies. I don’t think these are merely executions of adventure but ways in which we experience the ephemeral nature of our lives and our spirits. We are born into bodies and these keep us grounded. We are made up of matter—of water and stardust—but there is something about us that seeks to reconnect with the air, and with the lightness that is also present within us. It would be injurious to not recognize this quality about ourselves as substantial as well, even if not as easily measured, weighed or quantified. For it is this lightness of our beings that encourages us to take risks, to try to create, to find ways to suspend ourselves in mid-air, if only for a moment.

II.

Today, I read a modern day fairytale that was a transformation of “The Little Mermaid” by Hans Christian Anderson. This story takes place not underwater or in a fabled land, but rather, in San Francisco, a city I called home for three years. So I was immersed from the get go in being told of the Victorian on Divisadero—a street I lived one block away from, in another Victorian, during my time in “the City.” In this fairytale, a long-married but strained couple set up a huge water tank in their living room and take turns competing to see how long they can hold their breath before they must, inevitably, float up to the surface.

For me, the story was about both the beauty and danger of being underwater and the beauty and danger of allowing ourselves to rise up, to surface again.

Another focal point in the piece “What the Conch Shell Sings When the Body is Gone” by Katherine Vaz* is the aquatic ballerina Annette Kellerman. She was once called “The Ideal Woman” because the shape of her body mimicked the proportions of Boticelli’s Venus de Milo. But Kellerman was born with a defect in her legs and had to wear braces to walk. She was hardly an ideal candidate to be a ballerina. However, Kellerman found her physical limitations were completely resolved after she took up swimming. She created ballets underwater, her feet flicking in the same quick movements as other dancers did in the air, momentarily floating above the ground. The video I watched of her on youtube is in black and white and there is a dreamlike ethereal quality to it. She is visible and yet her features are awash. Her movements are clear but the video lacks sharpness. I found myself taken by the beauty she creates of appearing to be rooted in this underwater world. She holds onto items as she moves through the water but it is not a grasping.

When I was about ten, Disney’s The Little Mermaid came out. I memorized all the words to “Part of this World,” the song when the mermaid Ariel muses about the oddness of the human world and all of the things she wants but, by nature of her fins, cannot be a part of. She has collected trinkets from this world, but she has no context for them. She wants to be a part of a world that she does not understand. And while this story ends happily and the Anderson version does not, both rely on the prince’s decision and affection for their endings. In neither story does the mermaid herself have a sense of volition.

I think of Annette Kellerman, who is credited for creating and bringing to popularity the first one-piece women’s bathing suit, a full-length form-fitting jumpsuit. She needed to be able to move through the water and create art with her body so for practicality’s sake created a costume that allowed her to do so, and defied expectations for women in the early 1900s. I think of Annette Kellerman, who is credited as the mother of synchronized swimming. I think of Annette Kellerman, creating her dance underwater, the beauty of her movement and the ability to create the vision she had, without becoming wrapped up in other’s expectations of what she should do, how she should dance.

When you watch the video of her dancing underwater, you can see the grace of her movements and you can also see the tiny bubbles of air floating from her mouth to the surface. She is doing kicks and splits and backbends, she is forming her body into elegant shapes, and, she is breathing.

III.

In mining, flotation is a process whereby a mineral-bearing substance is concentrated into an ore. The raw substance is treated using chemicals so that the desired mineral articles attach to air bubbles and the air bubbles carry these to the surface of the pulp. Undesired minerals remain submerged.

The process is also called “frothing” or “froth-flotation” because once the desired minerals rise to the surface, the froth is then sweeped from the top, collected and distilled. This process is used for many minerals, most popularly, silver.

Frothing is done according to minerals “wettability.” The chemicals used are chosen to completely wet one of the types of particles while partially wetting the other type. It is the partially wet type that will attach to air bubbles and will lift up to become part of the froth.

Although initially developed for mining, the froth flotation process is now used for other needs of modern society, like treating wastewater, like de-inking paper so it can be recycled into new paper.

Images of froth flotation resemble the bubbling up of sparkling water, of soda, of hot springs. Except these bubbles are opaque. The minerals attach to the bubbles and color them shades of gray, of silver, of black, of copper, of brown. The mineral particles attach to the air bubbles, become part of them for a while, and they float for just a moment before they are then separated again, distilled out.

I have never been good at chemistry. I can get some of the basic concepts. I can memorize formulas. I can understand that matter can change in structure, in form. But I have never been good at understanding or identifying the precise moment when pieces of matter conjoin or divide, at being able to envision the exact time in which matter transforms, becoming suddenly more heavy or becoming weightless.

*published in the amazing collection, My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me